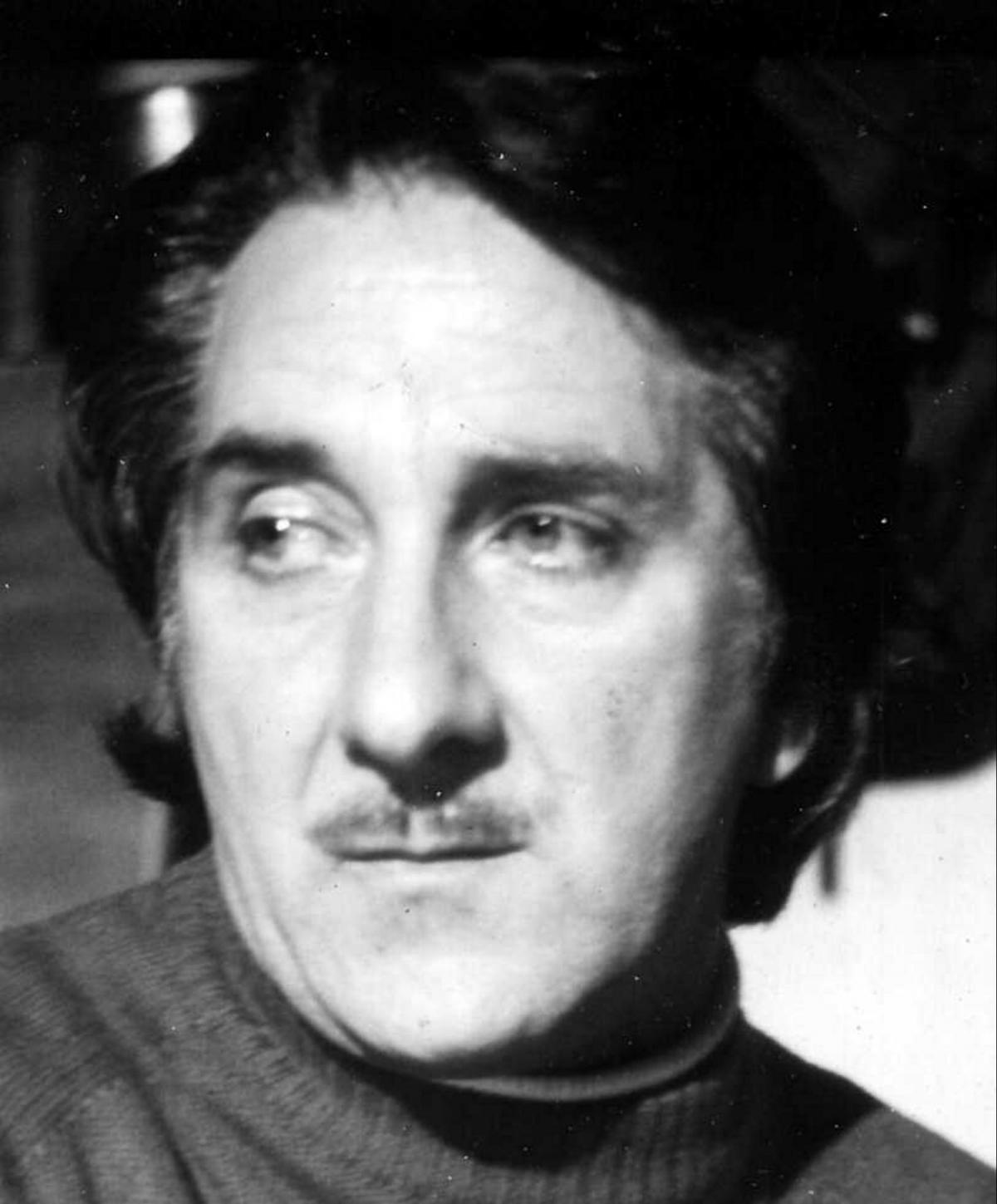

WE didn’t get to make our trip to Spain to follow the route, no doubt with many fuelling stops, which had led him to narrowly avoiding being garrotted for attempting to blow up the fascist dictator Francisco Franco. Instead it was a 20-year sentence, which he accepted with relief and took in his stride. Shortly before 2pm, a week past Saturday, life left my dear pal Stuart Christie. It was peaceful, his daughter Branwen at his side, the song Pennies From Heaven playing in the background, occasional sips of Glenmorangie between the morphine hits.

Stuart’s life may have been plastered with headlines, Britain’s most famous anarchist was the usual description, but the small print of it was what was important, his loyalty, not just to what he believed in but to his friends and family, his remarkable intelligence, his self-deprecating, droll and spiky humour. Physically he was also tall and handsome, totally imperturbable, probably from having faced the worst. He was someone whose best qualities most of us would strive to emulate, and fail. Branwen described him as her rock. He was.

I saw him last in February in Glasgow, we went for a drink or two in the Doublet on the edge of his native Partick, then to the Shish Mahal for a curry, where we planned the trip we would never take. The original one, viewed from now, had its moments of high farce.

He had told his family that he was going grape-picking in France, instead he was travelling to Paris on a single ticket and a handful of change to pick up explosives to deliver to comrades in Madrid who were planning to blow up Franco and his cabinet on a dais at Real Madrid’s Bernabéu stadium. The only French he knew was zut alors, which amused his anarchist hosts, and his Spanish was non-existent. He was to wear a bandage on his hand so his contact could recognise him and he had to be taught a phrase – me duele la mano (my hand hurts) – as a coded response.

He set out to the south with the plastic explosive taped to his body, hitchhiking and wearing a kilt so that he’d get lifts, which led to reports in the Argentine press that a Scottish transvestite had tried to kill the Caudillo. His last lift in France broke down just short of the Spanish border and Stuart had to push the car across, sweating and hoping the plastic would hold firm, under the gaze of the Guardia Civil in their shiny, patent, three-cornered hats.

The mission had been infiltrated by an informer and when Stuart handed over the package to Fernando Carballo Blanco, a carpenter who was constructing the dais and would place the charges, they were swooped on. It was August 1964, A Hard Day’s Night was top of the hit parade and Alec Douglas-Home was Prime Minster, doing economics with matches. The two were convicted on September 1 in a brief trial before a military tribunal, Blanco given 30 years.

It was undoubtedly international pressure and publicity that deterred the ‘court’ from passing the customary death sentence for ‘terrorism’, which was then carried out by garrotte, the medieval process of neck-breaking in a slow mechanical strangulation by a metal collar and a bolt through the neck.

Stuart was mildly roughed-up by Franco’s secret police but he was forced to watch his co-conspirator brutally tortured. Blanco’s father had been shot and murdered by Franco’s forces for being a trade unionist, driving his mother mad with grief and ending in an asylum. Although Stuart was released after just less than four years after an appeal by his mother, Blanco served 23 years. When I was contacted by his niece last week she denied that he had been a hero. “He just wanted to free the Spanish people,” she said.

Franco was an unapologetic fascist and dictator who led the overthrow of the Republican government, precipitating the civil war, with the blood of many thousands, and not just combatants, on his hands. As he put it: “Our regime is based on bayonets and blood, not on hypocritical elections.”

Stuart’s memory of the show trial, conducted in Spanish of course which he could not then understand, was of 11 army officers, heavy with medals, swords on the table in front of them, comprising what passed for a jury in a large, sticky, vaulted room. He said he felt he had been transported into the final act of some grand opera. “I was 18 years and six weeks old, a boy from working-class Glasgow and I’d never been to the opera,” he remembered.

He learned Spanish in the Carabanchel jail and sat A-levels (he’d have something to say about that now) and was sent money regularly from Britain but also from Spanish anarchists. The only English names they seemed to know were John, Paul, George and Ringo, so the donations turned up in these names and the authorities thought he was being funded by the Beatles.

He was released in 1968, got work as a gas fitter as Britain was converting to North Sea gas and inadvertently almost blew up a large part of Essex when he was unable to stop a massive gas leak.

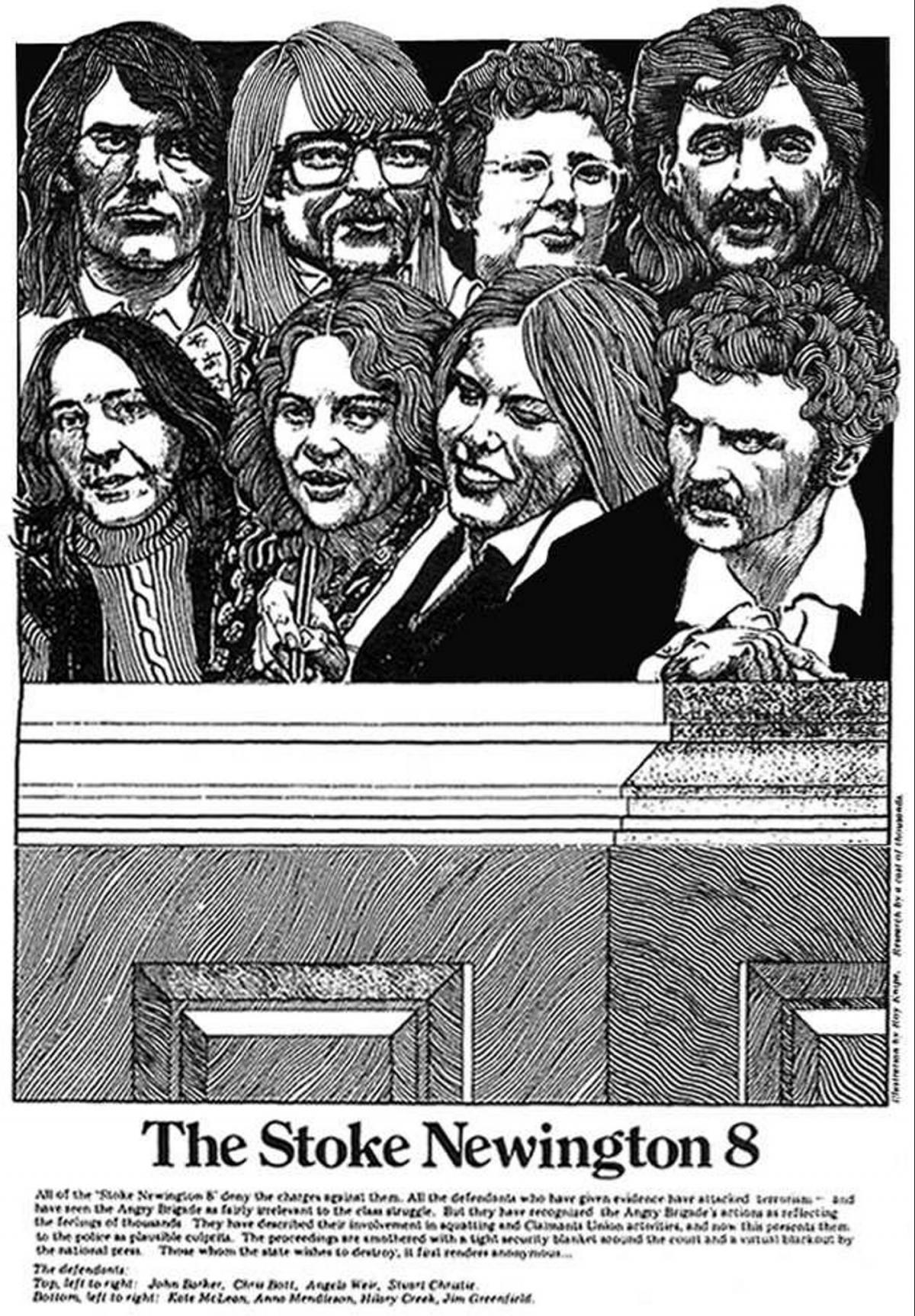

In 1972, after having been arrested and spending 18 months in jail on remand, Stuart was acquitted of being a member of the Angry Brigade, which had carried out a series of casualty-less explosions against Edward Heath’s government. He claimed, and the jury believed him, that the police had planted two detonators in his car. One of the four of the convicted Stoke Newington Eight, John Barker, said later about his own experience, “The police fitted-up a guilty man.”

Two years later Stuart and I holidayed in a remote cottage up a narrow, pebbled track outside Oban, where we walked, talked and sank a few malts in the evening round a roaring fire. At the same time a Francoist banker had been kidnapped by an anarchist group and a ransom paid. When Stuart returned to London he was warned by a friendly Special Branch officer that he wasn’t safe and should get out of town, which he did with his wife Brenda, first to Yorkshire and then the remote Orkney island of Sanday, to a house called Over the Water.

Then, the island might have been some prototype of an anarchist society, in that it was peacefully, if bibulously, self-governing, with only an occasional police presence coming in by ferry from the mainland, the officers’ travel well telegraphed. I’m not sure anyone there bothered with car insurance. On one occasion a man was arrested for alleged drunk driving, the local doctor refused to test him and by the time the coppers had somehow managed to hire a boat and take him to the main island he was sober.

I visited him and Brenda often, and many an evening was spent in the Kettletoft Hotel bar, often with instruments and a sing-song going, irregardless of conventional closing time, until the last patron exited. On one occasion two bold officers turned up and insisted that the bar was cleared at 11pm, to the considerable ire and disgruntlement of those of us who considered the evening was just beginning.

There was a party to go to and Stuart and some others light-heartedly berated the two policemen now sitting in a car outside with the windows down. While he and they kept the officers occupied someone crept round the back of the car and let the tyres down. (And if the statute of limitations on this has passed I will confess.) We sped off waving.

Stuart and Brenda spent seven years on Sanday, Branwen was born there, and from the island he launched his publishing house the Cienfuegos Press (named after the Cuban revolutionary Camilo), a major publisher of anarchist literature, and a radical newspaper, the Free-Winged Eagle. The local minister of course denounced him as the “anti-Christ”.

Stuart Christie was born in Partick to a hairdresser and a hard-drinking trawlerman, Albert. He was named Stuart after Bonnie Prince Charlie, “the only man in history to be called after three separate sheepdogs,” according to fellow Partiquois Billy Connolly. When he was six his parents went to friends for a drink, his dad was given a glass of sherry which he looked at in disgust, poured down the sink and walked out the door without saying a word. “The joke was that he had gone for a packet of fags, but that’s the last time we saw him until he turned up 20 years later,” Christie recalls.

By then Stuart had a half-sister, Olivia. But the formative influence on him had been his granny Agnes McCulloch Davis, with whom he did most of his growing up on Arran and in Glasgow. He described her as the moral barometer in his life, “and she provided the star I followed. She kept me on the straight and narrow.” Well, with a few well-publicised detours!

His partial autobiography, a compilation of three self-published volumes, was appropriately called Granny Made Me An Anarchist, in which many of the truths are told. It’s a rollicking account peppered with cultural and political reference points, from the Jeely Piece Song, to Leslie Howard, Buñuel and Just William. It’s also extremely funny.

He also wrote a trilogy of novels ¡Pistoleros! The Chronicles of Farquar McHarg, about a fictional Scottish anarchist born in 1900 who became involved in the Spanish civil war, which weaves in actual happenings and some of the principal villains of the time. Stuart also managed to pack in a degree in history and politics along the way.

Brenda Christie died in June last year, nursed by her husband and earlier this year Stuart moved to Colchester to be near daughter Branwen and her girls, his granddaughters Merri and Mo, for too short a time. He had previously fought cancer, this time it was lung cancer which spread to the bone. His suffering was mercifully short.

I’ve been with him when he’s been introduced to people and occasionally the response would be, “Not that Stuart Christie?!” To which he’d always answer, “The West of Scotland ballroom dancing champion?” Some poor unfortunate had the same name.

For the record he was a terrible dancer.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel