Why should the vast majority of people have their freedoms curtailed in this pandemic, their livelihoods put at risk, their businesses flounder or fail, thousands sent to the dole, queue, mental health threatened, when the risk of catching Covid is so vanishingly small?

That’s a question many have answered for themselves, judging by the numbers who are told to self-isolate and don’t – currently around 90 per cent – and the others who flout in small ways, by travelling out of local lockdown, by visiting relatives or lovers, or going on holiday, rather than the headline-making irresponsibility of holding mass raves.

The facts are stark. Scotland during the week broke through the Covid-19 5,000 deaths mark. Nonetheless, these men and women who died from it lived, on average, two and three years longer than normal life expectancy. In Glasgow, that jumps to nearly six years.

The average Covid male death was 79, whereas life expectancy nationally is 77, and women 84, compared with 81. In Glasgow, with the lowest life expectancy in the country, men die at 73.6 years and women 78.5.

Unpicking the figures a little more, three-quarters of the deaths occurred in over-75s. No-one under 15 has died, just 34 under 34, and 447 between the ages of 45 and 64.

Of course, behind every statistic is a tragedy, a loved one lost, heartbreak and suffering for the family watching a partner or a relative die, often in the most harrowing way, and dealing with the consequences. And, just as obviously, everyone should take the sensible health precautions to avoid spreading infection.

Burns wrote that facts are chiels that winna ding, but it really matters which ones you select and how you ring them. The Covid death figures in Scotland have wide parameters, including where a person dies within 28 days of having a positive test, or where it is mentioned on the death certificate, as either an underlying cause or a contributing factor. Only 8% of victims had no pre-existing condition. So, in a large number of these deaths – we don’t know the exact number – the primary cause of death was not the infection, although it may have hastened the end.

We know the personal effect in the grief and pain of a relative or partner lost. But how do you measure the economic cost of a life taken by this pandemic?

Be sure that statisticians in Government are doing just such a cost/benefit analysis, whether it is admitted or not, and that, in part, this is influencing politicians in deciding what measures to impose.

Is it the total amount of relief poured into the economy, or the hit on gross domestic product, divided by the fatalities? Or some other metric? Scotland’s GDP has dropped by 20% through Covid – that’s about £9 billion, so do the maths.

It was clearly the threat to the Treasury, and the political danger

to Boris Johnson, which initially

saw the UK Government flirt with so-called herd immunity. Sir Patrick Vallance (where is he?), the Government’s chief scientific adviser, said they would suppress the virus “but not get rid of it completely” – while focusing on vulnerable groups, like the elderly.

He added that since the virus caused milder illness in younger age groups, most would recover and subsequently be immune. This “herd immunity” would reduce transmission in the event of a winter resurgence. Neither turned out to the the case. There has been a huge second surge and immunity has been found to be temporary.

On one of his daily TV appearances, Vallance said that “probably about 60%” of people would need to be infected to achieve herd immunity. The message seemed to be: “Keep calm and carry on and get Covid.”

The tactic of relying on a potentially deadly infection to create an immune population predictably caused outrage. But Johnson, his colleagues and advisers, still initially shrank from a total lockdown, while countries like China and New Zealand had employed it to huge effect, including closing the country to visitors.

New Zealand has a population around the same size as Scotland and has had 25 Covid deaths. That’s because they closed the border to travellers. You still can’t go there unless you’re a citizen and still you have to go into what they call managed isolation – 14 days’ quarantine in a government facility. It works, but of course we couldn’t do that.

Johnson and Vallance, following the same script, both mouthed that if there was a total lockdown there would be behavioural fatigue and people would get sick of the draconian measures, although almost 700 behavioural scientists demanded to see the evidence for that in an open letter to the Government.

The UK delayed lockdown for over two weeks in March, trying to preserve the economy, before the steeply rising number of cases forced them into a policy U-turn. Who knows how many were infected and died in that window?

Sweden was the only European country to stand alone and follow a Scandi version of herd immunity, although the public health authority strongly recommended social distancing, working from home and avoiding unnecessary travel, among other precautions. Perhaps because the Swedes put greater faith in their government than we do, compliance was high.

Even as infections surged in April and May in Sweden test-and-trace-programmes were not boosted, but on the grounds that they would not be effective in dealing with large-scale virus spread. In mid-September, for the first time, the advice changed – that people should now quarantine themselves if someone in their household becomes infected.

Still no lockdown, however, and despite the observance of public health guidelines Sweden’s infection rate is now eight times higher than neighbouring Finland and triple Norway’s.

Hospitalisations from Covid-19 are also rising faster than in any other country in Europe, and deaths are mirroring the UK’s in age profile, with 89% of the dead over 70.

Herd immunity may not have worked for the Swedish population – there’s no evidence that it ever has – but it has worked for their economy.

GDP may be down by 8.5% through Covid, but that is, by some margin, smaller than any other country in Europe, and less than half our 20% Covid consequence.

There is some evidence, if partly anecdotal, that the new tiered measures in Scotland will not have the same observance as in Sweden, and that behavioural fatigue is setting in. The system, based on council areas, is causing some risible anomalies.

On Tuesday, I was having a late lunch in Kilmarnock when Nicola Surgeon (anyone seen Jason Leitch?) announced the stricter new measures. We were discussing it when the woman at the next table, who had heard us, asked: “I’m going on holiday at the weekend to Spain from Prestwick Airport, is that illegal?”

No, it isn’t, but driving to the airport is! Kilmarnock is in tier four lockdown, and Prestwick, North Ayrshire, is in comparatively free tier three.

The first national lockdown flattened the curve, although slightly and temporarily, and a second autumn and winter wave was predicted.

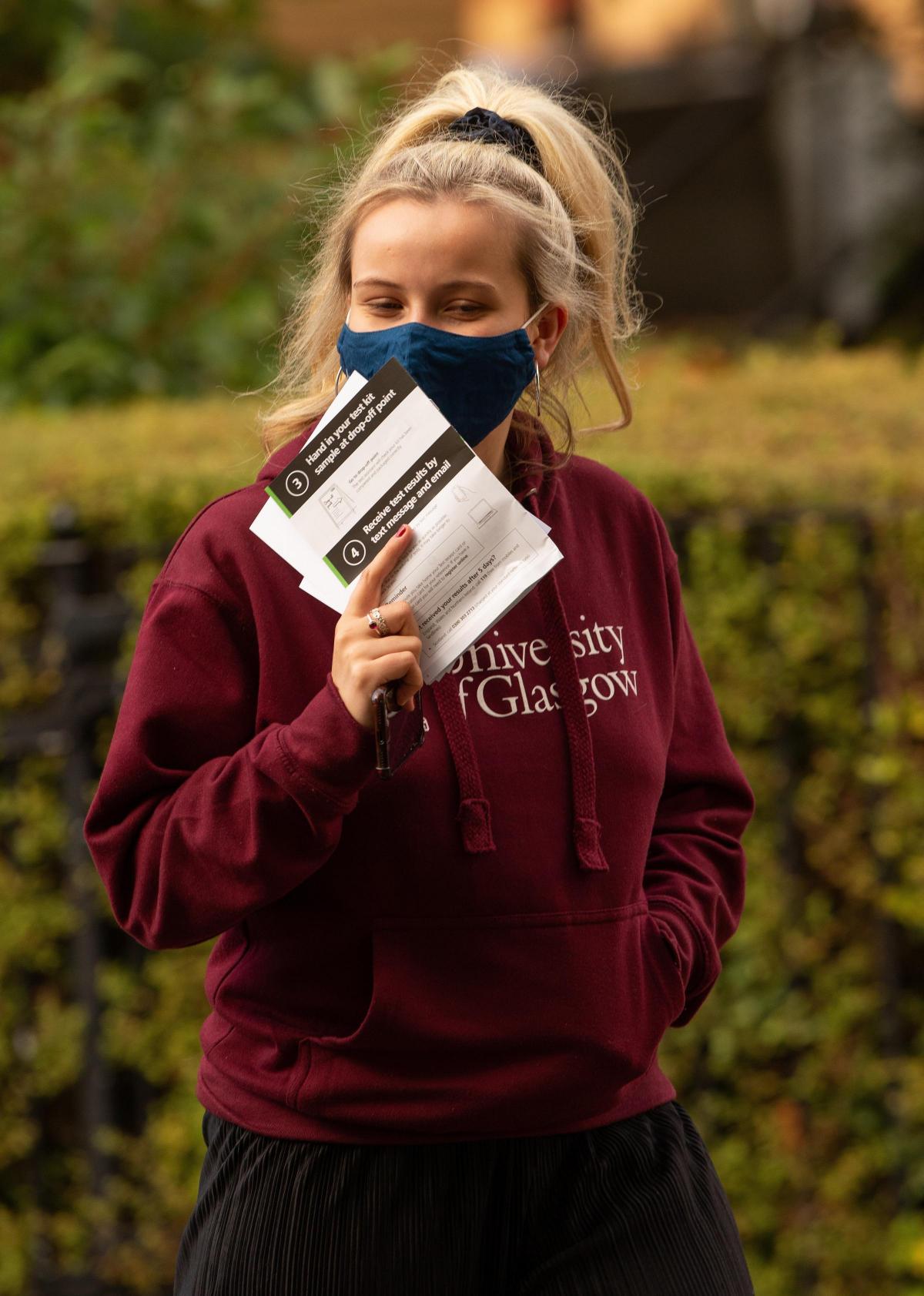

Measures, like the closing of pubs and restaurants, banning spectators from most sports, have not stopped the second spike, while schools and universities remain open.

Most pupils and students are unlikely to be badly affected by the virus, other than carrying it to the most vulnerable, people which seems a fairly crucial other.

There’s an Orwellian solution – age segregation, isolating the old and the vulnerable in institutions. We tried that with care homes and it proved to be a remarkably efficient way of killing a large number of people.

This all began in fudge and will no doubt end that way. The policy, if it can be so described, has been an uneasy trade-off between economic activity and human lives, with the former having rather the better of the deal.

We’ll bodge it all the way to the vaccine, and no doubt beyond.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel