We have all become rather more familiar with our home furniture and all its quirks these last 12 months than we were before. Kitchen tables adapted as school desks, wonky shelves in tiny cupboards as “home offices”, the living room sofa as staff room or “break out space” to coin what may or may not be modern office parlance. Break down space might be more appropriate, of course, for anyone frazzled after a year of juggling “remote learning” and work deadlines.

One could imagine, as such, that for the bespoke furniture makers of the Scottish Furniture Makers Association, lockdown could have been something of a boon, sorting out all those awkward corners and useless tables which many suddenly found were just entirely what they did not need to thrive in a home-work environment. “Some of us did get a few more commissions,” says Mike Whittall, Chair of the SFMA, which next week opens an online exhibition celebrating the 20th anniversary of its founding. But getting commissions, of course, depended on whether you still had a workshop to work in.

Adjust/Adapt, which was to have taken over the first floor of the City Art Centre this month, was a call to furniture makers for a response to lockdown, a physical manifestation of how lockdown has affected makers, and the effects, too, of the climate crisis we simultaneously find ourselves in. Photographed in the atmospheric Leith Theatre in Edinburgh, the SFMA present the exhibition in partnership with Visual Arts Scotland to show ten selected VAS artworks, of both applied and fine art, alongside the 25 unique furniture pieces from SFMA members, curated by two specially-commissioned photographers as theatrical still lives with specially painted backdrops.

The photographers are in Leith Theatre as Whittall and I speak, the capacious venue tucked behind Leith Library (itself currently functioning as a Covid test centre, its books hidden behind high screens and masked ushers) which has in recent years been brought back to life as a venue for gigs and the Edinburgh International Festival.

Works include Tom Addy's Isolation Chair, a boxed in, upright wooden seat that looks related to an Orkney Chair. “When you sit in it, you do feel isolated from things which are around you,” says Whittall. There is a hinged, pull-down wall desk from Kirsty MacDonald, with all the compartments one might expect in a stand-alone desk, and Janie Morris' two-sided Love Desk, inspired by all those people who suddenly found themselves working on opposite sides of the kitchen table to their partner. Whittall's own work is a finely-finished desk. “It was conceived as a work desk that could adorn a living space. It's functional, but a decorative piece as well. It can take its place as a nice piece of furniture.”

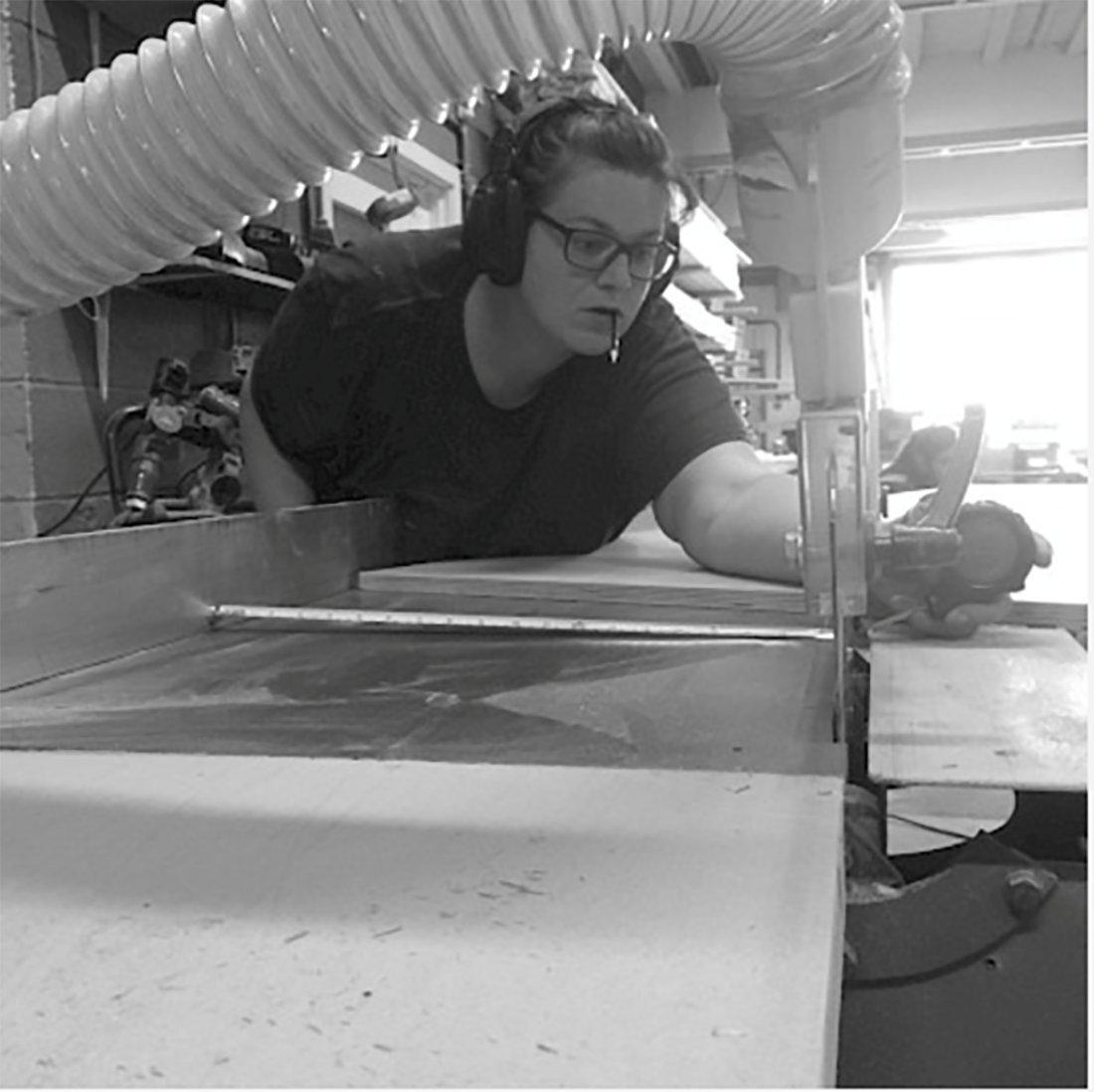

Whittall points out that members who had access to their own workshops at home were among the luckier ones. “There are some of our members who work in shared workshops, and certainly in the first lockdown, when it was 'bang!' that was it, they were unable to go to work. It sent quite a shockwave through the membership. People were not able to get in to their workspace and finish their jobs. Things were desperate. None of us were able to visit clients, which is such an important part of the process, because you need to see the space where a piece is to go...”

“I remember seeing one of our makers sharing pictures in the early parts of lockdown last year, of putting up a makeshift work bench in the kitchen,” Whittall chuckles. “There was a limit to what he could achieve, but when we were all told to stay at home, he just grabbed as many tools from his workshop as he could fit in his bag, thinking he could at least do something. It's surprising what you can achieve. When you haven't got access to just the right tool, you have to make it work with a different tool.”

Alongside maker-videos giving behind-the-scenes glimpses of workshops and creative practices, there will be three online panel sessions, taking place throughout April, that will cover different aspects of furniture making, from the sustainability of resources – an absolutely key concern of the SFMA, many of whom use local wood, and sustainable Scottish hardwoods – to a workshop on gaining skills, and another on how a client might work with a maker. “The public will be able to come to all of these as if they were in the room” says Whittall, who points out that the positive thing about moving things online is that you can get a good range of speakers who would have been unlikely to all be able to attend if they'd had to get to a particular venue.

“We obviously like to exhibit our work physically, so that people can see it and walk around it and touch it. And we will really miss talking to people. But I will say, having done what felt like this brave thing, with great support from the City Art Centre, it's opened up interesting impossibilities that we could never have imagined in a physical space.”

Adjust/Adapt: Scottish Furniture Maker's Association. 27 Mar – 24 Apr. www.scottishfurnituremakers.org.uk and www.edinburghmuseums.org.uk (Venue: City Art Centre)

Critic's Choice

IF bats, via the unwitting intermediary of an equally innocent pangolin, and the great guilt of human-caused environmental destruction, have been postulated as the viral originators of the global pandemic we’ve spent the past 12 months grappling with, then they are, now, the centrepiece of a work in progress from visual artist and composer Hanna Tuulikki.

Commissioned to write a new composition by Hospitalfield, the arts centre in Arbroath, Tuulikki has put out a public call for recordings of bat echolocations to populate a new public library and become part of her composition. Tuulikki is interested in the crossover between the bat and non-human world and our own, which brings to mind a radio documentary I once heard on the ability of humans, particularly those with impaired vision, to employ their own echolocation, helping them subconsciously map their environment.

Bat echolocation, as many will know, is a series of high pitched noises, usually too high for humans to hear, that help these winged mammals navigate their nocturnal world. Tuulikki equates this with the world of dance music via the philosopher Timothy Morton, who speaks of dance music as “becoming aware of the fact that what is called present is in fact this pulsating, moving-without-travelling, vibrating thing, or group of things... flowing to their own rhythm”.

Her composition, part of a project entitled Echo in the Dark, will aim to investigate the “ecological intimacy” between species,

both existing in a degraded environment, perhaps finding a way towards ecological co-existence.

Whether you have your own bat detector, or have otherwise tried to record bat echolocation calls, do get in touch with Tuulikki if you would like to contribute calls from any species of bat to this new work.

http://www.hannatuulikki.org/echointhedark/ To contribute bat echolocation recordings, or for more information on doing so, please email inthedarkecho@gmail.com

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here