New think tank says findings underscore need for ‘just transition’ to net zero, so poor who contribute least to climate change don’t shoulder unfair burden of environmental costs, writes Neil Mackay, Writer at Large

THE gulf in carbon emissions between Scotland’s richest and poorest households is revealed today for the first time

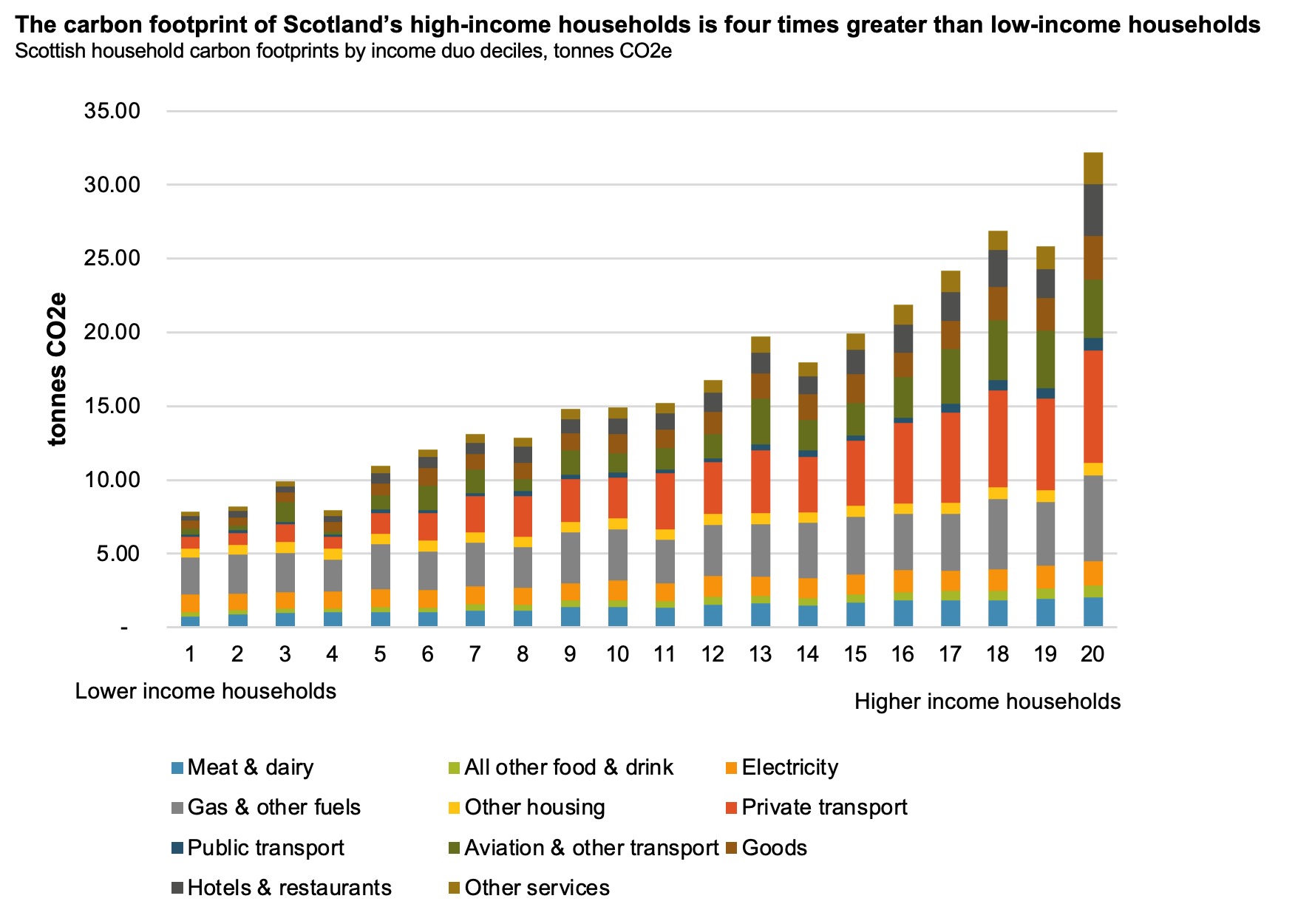

The think tank Future Economy Scotland (FES) has given The Herald on Sunday exclusive access to new research which shows how the richest households leave a carbon footprint more than four times greater than the poorest households.

The research covers a host of areas including food, electricity, gas and fuel, housing, private transport, public transport, aviation, household goods, wi-fi and phones, and the use of hotels and restaurants.

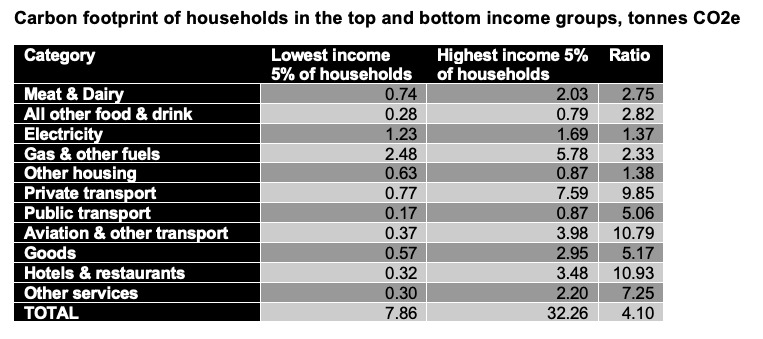

On aviation, the richest 5% of households leave nearly 11 times the carbon footprint of the poorest 5%. The same is true for hotels and restaurants. For private transport – using cars – the richest 5% leave almost 10 times the carbon footprint of the poorest. For public transport, the disparity is five times higher, accounting for the wealthiest households using trains more for business travel.

For all food and drink, including meat and diary, the richest 5% expend almost three times the carbon emissions of the poorest. For gas, the rich carbon footprint is more than double compared to the poor.

For what’s termed “goods” – items like TVs and fridges – the rich leave five times the carbon footprint of the poor, and for “services”, which includes wi-fi and phones, there’s a sevenfold increase between rich and poor.

Figures also show that the carbon footprint of the richest 5% is double that of middle-income households.

When it comes to electricity, however, the richest and poorest households leave effectively the same carbon footprint, with the rich only marginally higher in terms of emissions. Significantly, this reveals the dire effects of the cost of living crisis on the poor, according to FES, and shows that the poorest households, with much smaller incomes, are spending roughly the same as the richest households on heating their homes and cooking.

The co-directors of Future Economy Scotland – a new think tank which researches how Scotland can move to a fairer, greener economy – say the findings underscore the need for the transition away from oil and gas to be socially just. The poorest, who contribute the least to climate change, shouldn’t be made to shoulder an unfair burden, they say, and the rich should pay their proportional share.

The Herald on Sunday sat down with co-directors Laurie Macfarlane and Miriam Brett to discuss what the Scottish Government must do to ensure the shift to a green economy doesn’t unfairly impact the poor.

Miriam Brett and Laurie MacFarlane of new Scottish think-tank Future Scottish Economies. Photo: Gordon Terris

Unemployment

Macfarlane and Brett applaud the Scottish Government’s target of reaching net zero by 2045 – five years ahead of the UK Government. However, they warn that the wrong approach could replicate the pain Thatcherism caused in the 1980s. What’s needed is a “just transition” that doesn’t hurt poor communities, or increase unemployment.

“Across Scotland, we still see the scars of the rapid deindustrialisation we had decades ago,” says Macfarlane. “As we look ahead to another big transformation we must make sure we’re not repeating the mistakes of the past.”

FES says: “The cost of transition must be fairly shared. If it’s not, we’ll just end up exacerbating the inequalities we already have, and disproportionally impacting those on lower incomes, which could undermine support for a just transition.”

Brett adds: “Inequality and the climate crisis are inherently linked”, as shown in the think tank’s new figures, with the rich creating more carbon than poor and middle-income households.

“Higher-income households are responsible for the majority of emissions. We can’t create a greener economy unless we create a fairer economy.”

Disconnect

THERE is “disconnect” between the Scottish Government’s net-zero goal and “the level of ambition regards policy”. In Scotland, renewables have been scaled up, “but nowhere near enough”. Key climate targets have been missed in four out of the past five years, Macfarlane points out.

The Scottish Government must embrace “bold, transformative policy” if green goals are to be achieved fairly. FES says the government must start focusing on creating “secure green jobs” and “reskilling and retraining workers” so they can shift away from carbon-intensive industries, ensuring areas like “Aberdeen don’t become another Ravenscraig”.

Brett says achieving net zero by 2045 requires a “massive and rapid shift in Scotland’s industrial base … You can transition to net zero in a way that doesn’t carry workers with you, doesn’t provide a secure, sustainable future for [communities like Aberdeen], that doesn’t create good, green, well-paid unionised jobs, or you can embark on a just transition”.

She adds: “The scars of the last wave of deindustrialisation [under Thatcher] are still visible today in child poverty levels. We’re at a fork in the road.” Scotland needs a “roadmap” so the poor, and communities dependent on oil and gas jobs don’t suffer.

It’s a fine balancing act. Our large fossil fuel sector needs phased out in a “managed, controlled” way, says Macfarlane, while green, secure jobs are created as replacements. “If we just leave this to the market, there’s no guarantee those jobs will materialise and this will lead to dislocation and potential regional decline.”

“The government promised there would be huge numbers of jobs created in offshore wind. Those haven’t really materialised,” he adds. In 2010, FES says, the Scottish Government projected 28,000 workers would be employed in the offshore wind sector by 2020. However, Office for National Statistics figures showed only 3,100 workers by 2021, just 11% of the projection.

The key problem is that the jobs made available through offshore wind are “largely in manufacturing and construction”. However, in Scotland, “we haven’t developed the capacities and supply chains” for those jobs.

“So most of the work has gone to overseas companies, and the benefits are accruing to companies elsewhere.”

Air source heat pump installers install an air source heat pump unit into a 1930s built house

Industry

BRETT says Scandinavian nations have “massively scaled up renewable generation alongside creating huge numbers of [green] jobs, which is where Scotland has fallen short”. We need to “reinvigorate our domestic manufacturing capacity and maximise domestic supply chains. There’s huge opportunities there for job investment and exports”.

A just transition, says Brett, must happen in a way that “transforms” industry without increasing “poverty and inequality”. A good example, she says, is public transport. Affordable public transport in many European nations encourages less car use without hurting the poor. The best policies from government would “reduce poverty while decarbonising the economy”.

Macfarlane turns to the ScotWind deal as an example of policy gone wrong. ScotWind saw leasing rights for offshore wind development sold for £750 million to investors. “It was a missed opportunity,” says Macfarlane. “We replicated the mistakes of the past made with oil and gas. There was this huge resource and we basically decided to hand it over to global multinationals for not very much return”. The oil and gas giants which took options in ScotWind will “generate huge amounts of energy, and all we got was £750m – it’s peanuts”.

FES is working on what ScotWind could have generated for the public purse, but estimate it may have raised “billions and billions” more if done differently. The Scottish Government should have taken public equity stakes in the deals so that “a share of the profits came back and could be reinvested” in green job creation. Another ScotWind round is due and FES says “lessons must be learned”. ScotWind also had “very little conditionality regarding investment in Scottish supply chains”. In other words, there’s “weak” compulsion for overseas firms to use Scottish companies as part of their business. That means “loss of investment domestically in Scotland. That’s a real blow to our chances around a just transition and green job creation”.

Macfarlane says Denmark is to take 20% public equity stakes in a number of major offshore wind projects in its waters. Foreign companies which bid for ScotWind, unsurprisingly, “saw it as a very good deal”. ScotWind was “heavily” influenced by investors. Industry “helped shaped the deal” for a “risk-averse, cautious Scottish Government”. As a result, many now see it as “a terrible deal”.

One of the big winners from ScotWind was Sweden’s publicly-owned company Vattenfall. It’s a world leader, says Macfarlane, “because of the support over years from the Swedish state. Now they’re winning contracts for our offshore wind, the profits from which go back to Sweden”.

He adds caustically: “When it comes to energy, the Scottish Government isn’t against public ownership, it seems, unless it’s Scotland doing the owning.”

Mistakes

Brett drew comparisons to ScotRail, prior to nationalisation, being owned by Abellio, the Dutch state-company. “It’s clear which countries have industrial strategies, and which countries decimated their manufacturing base and have quick fire-sales of national assets”. We must “reflect”, she says, “on the mistakes of the last 40 years”.

She says that when it comes to natural resources like wind, “the taxpayer must benefit significantly. There must be rebalancing of who has a stake and say in this process, and who shares fairly in rewards”.

Brett adds that as our devolved government has “limited borrowing powers, we must get really creative about revenue-raising, because a comprehensive just transition is going to take an awful lot of public investment”.

Scotland failed to learn from the mistakes around North Sea oil and gas, the think tank says. In Scotland, “mainly oil and gas executives” in private industry benefited. Norway, however, has similar amounts of fossil fuels as Scotland, but the difference between the two countries “is stark”. Norway has the world’s “largest sovereign wealth fund worth more than a trillion dollars, which provides return to the public exchequer every year”.

Brett says some regions of Scotland have been bold when it comes to renewables. In North Ayrshire, derelict land is used for publicly-owned onshore wind and solar farms.

She says it will “generate 277% of North Ayrshire’s energy needs. They can sell the excess, using that funding to reinvest in important issues for the community. It’s a common-sense, democratic

approach, not focused on funnelling as much profit as you can into shareholders’ hands”.

table

Anxiety

PUBLIC “anxiety” around the risk to jobs, through the transition to net zero, and the possible financial impact to households of installing heat pumps, are, Brett says, “very reasonable”. However, she also notes some polling shows even oil and gas workers “overwhelmingly support” moving to net zero if the transition is “just” and green jobs exist to replace old fossil fuel jobs.

Offshore workers want to safely transition to green employment, Brett adds.

However, there is “lack of progress” when it comes to “skills transition” – in other words, more training is needed so workers can move into renewables. In terms of the number of houses which need retrofitted to meet net-zero targets, Scotland “just doesn’t have enough trained people”.

FES suggests local authorities set up municipal companies to train and employ new workers for tasks like retrofitting thereby boosting employment, improving housing, and helping meet climate commitments.

That requires “direct government involvement – it needed to happen yesterday”.

Manufacturing

THERE is a “lack of domestic manufacturing capacity. The current jobs that are created in renewable energy pale in comparison to the number of jobs in oil and gas”. Most of the technology and hardware used in green energy is built overseas.

“An awful lot of the time, decision-makers bury their heads in the sand,” Brett adds. Scandinavian countries, she says, focused on scaling up green jobs in domestic manufacturing, as well as “related supply chains”. Building a manufacturing base in “green steel” would supply both wind turbines and retrofitting.

This isn’t happening as the UK government “absolutely decimated our manufacturing base”. There was also underinvestment and a lack of any coherent industrial strategy coupled with privatisation. That, says Macfarlane, “hollowed out” Britain.

Most of the hardware used for solar panels and heat pumps is made in China, Germany or Scandinavia, he adds.

The Scottish Government is still drafting its “net-zero industrial strategy”, despite aiming for net zero by 2045. Nevertheless, the move towards creating a strategy presents an opportunity for “a joined-up, co-ordinated approach to a just transition”.

Without a net-zero industrial strategy, Scotland is “missing an overarching comprehensive plan to get us from where we are today to where we need to be”.

Brett says the Scottish Government’s climate and economic “objectives” are “actually quite strong”, but “the policies required to meet those objectives are sometimes falling short”. Scotland must “elevate the level of policy ambition”.

Macfarlane adds that creating the green energy strategy is an “opportunity to be really bold and ambitious”. However, “if it’s just another set of words on paper, then obviously that’s a big missed opportunity”.

table

Heat pumps

THERE has been much talk about the costs of the net-zero transition, such as the installation of heat pumps, hitting households. “These are political choices,” Macfarlane says.

“How costs are shared is hugely important. On one extreme, you could have a situation where for heat pumps you say the cost is on every individual household – maybe with loans at a commercial rate of interest. That’s putting a huge amount of cost on the individual, though, particularly low-income households.”

Alternatively, a fair policy would see “government grants and maybe 0% loans from the Scottish National Investment Bank spread out over a long time. The distributional impacts of those two approaches are very different. The question is how do we do this in a way that’s fair and just”.

Those “in higher income brackets, with higher emissions” could shoulder costs, while those with lowest incomes could get grants, and middle-income households receive 0% loans.

Brett warns against the government pulling levers to achieve net zero which “drive inequality”. Rather, government climate policy should reduce inequality. Retrofitting social housing would cut energy costs for low-income families and prevent illnesses linked to poor accommodation.

There has been criticism of the Scottish Government for failing to adequately explain costs and financial support available around issues like heat pumps. Macfarlane says poor political communication “is a risk to the wider just transition agenda because if you say to people ‘OK, this is what we must do’, but you either don’t explain it, or provide the mechanism to make it feasible for them, it can really undermine support”.

Taxation

SCOTLAND must “answer the question: how do we pay for this”. That means looking at a “whole suite” of taxation changes, from making income tax more progressive and redistributive, to reforming council tax, new taxes on wealth and land, and addressing business rates exemptions.

FES suggests introducing a “frequent flyer tax” to rebalance the differential between rich and poor in aviation carbon emissions.

Due to the rise of “greens lairds” – private investors getting rich from carbon offsetting like tree planting – there needs to be changes to land ownership, FES says. The government’s consultation on the forthcoming Land Reform Bill “isn’t as strong as it could be”.

Large tracts of Scottish land are owned privately. The consultation on the upcoming bill suggests subjecting new land purchases to public interest tests, but not existing landholdings. If new land purchases are deemed against the public interest, they can be stopped. The same should apply to existing landholdings, FES says.

If that happened huge landholdings could be broken up, bought by communities, and used for tree-planting or peatland restoration to offset carbon, with profits returning locally for green investment.

Macfarlane says allowing “London asset managers” to dominate isn’t “consistent with a just transition. Is that the best way to deliver nature restoration or benefits to local communities?

Will it create well-paid local jobs? The answer for us is ‘no’. It’s not inaccurate to say that it’s a kind of PFI-for-nature approach”.

He adds: “We’re potentially having the government spend money to underwrite private investment. We need a much more community-led approach rather than have benefits extracted by absentee investors.”

Politics

HOLYROOD politicians need to try to work together and achieve consensus on the policies needed to take Scotland to net zero, rather than wage war on each other, FES says. Macfarlane and Brett have met with government representatives, civil servants and a variety of Holyrood parties. Both say they are “encouraged by the response” and believe animosities can be set aside and good policies passed at the Scottish Parliament.

Despite the towering challenges, both remain “hopeful” that the Scottish Government will make the right decisions so the country can achieve a just transition to net zero.

Brett says: “In terms of the intertwined challenges we face, though, messing about on the margins of economic policy just isn’t going to suffice –neither is simply ameliorating the worst excesses of the current broken model. We’ve also a very limited time in which to deliver a just transition – so there’s no choice but to be bold and ambitious.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel