Natalie Logan MacLean remembers how she felt when she was about to visit Barlinnie for the first time She knew its reputation as the worst prison in Scotland and had heard all the stories about the conditions, the violence and what the place could do to people It’s fair to say the emotion she was feeling when she first went to the building was fear. She was terrified.

Then she got inside, met some of the prisoners, and started talking to them. She found that a lot of the guys ended up in trouble because of what they had been through during their childhoods – and Logan MacLean knows herself what that can be like. She also saw men come in and out of the place for the pettiest of crimes – stealing a steak from Lidl – and started to see the need for the whole dysfunctional, expensive, counter-productive system to change.

Driven by the desire to improve things – and driven too by what she had been through in her own life – Logan MacLean set up a charity called Sisco which works with prisoners in Barlinnie to help them recover from drugs. She now runs a regular Recovery Café and works with the men to get to the reasons for their behaviour.

Sometimes, she’ll ask them to remember what they were like as a kid and what they wanted to be when they grew up (interestingly, they’ll often say policeman). The fact they ended up in Barlinnie instead – sometimes over and over again – is the key to working out how we can change things.

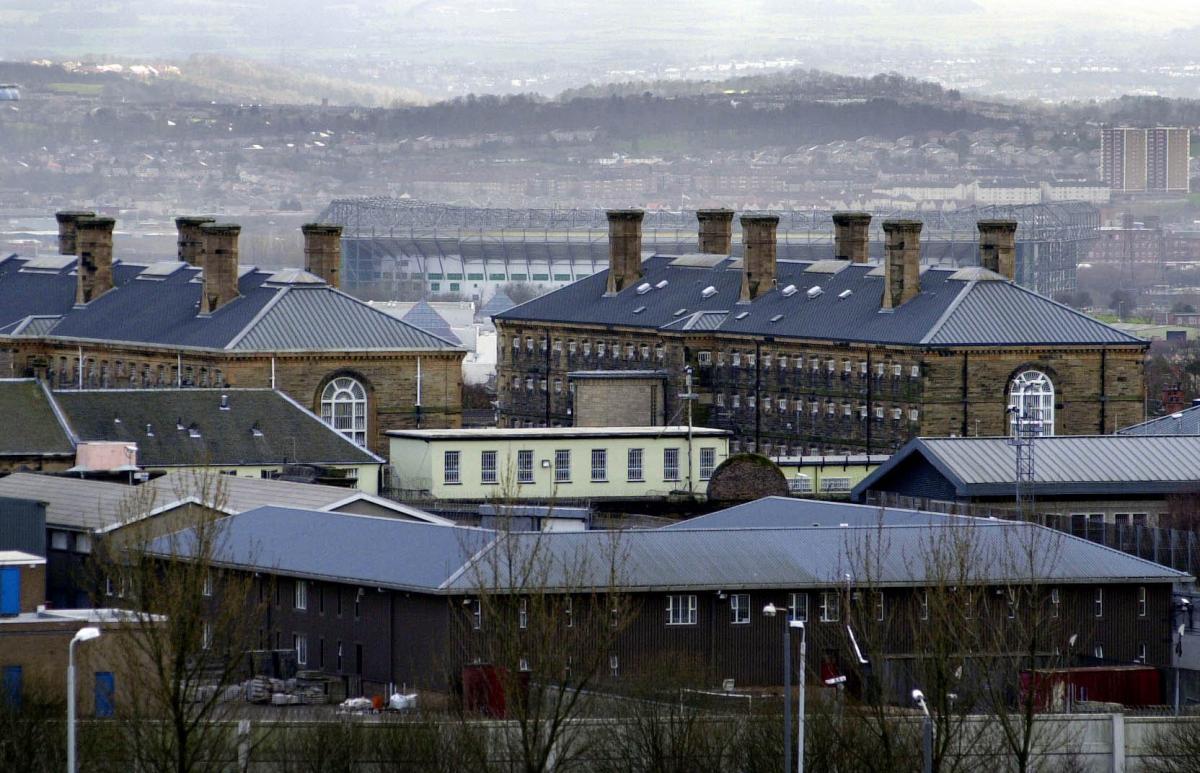

And now is a really good time to raise the question. Barlinnie will be closing for good soon and a new facility, HMP Glasgow, will be built to replace it on a 54-acre site in Provanmill. In many ways, it will be a radical change: the original Barlinnie dates back to the 1880s and, with overcrowded conditions that have often been condemned as unfit for purpose, it is still recognisable as a Victorian prison and still based, some would say, on Victorian principles.

No hard cells

THE new jail will be different, however. On the outside, the plans by the construction company Kier make it look very un-prison-like indeed. There are beautiful grounds and a big glass front that makes it resemble a company’s headquarters rather than a prison. Inside, there will be lots of changes too Barlinnie is notoriously overcrowded – it was built for 1,000 men but houses closer to 1,500. The new prison, by contrast, will have single cells and may have phones and computer screens in the rooms too In many ways, it will be a radical departure. The question is: will it be radical enough?

There are some who think that the whole idea of building something like HMP Glasgow in the first place is flawed. Keith Gardner has decades of experience working in prisons, including with inmates who have committed sexual offences. He has also run community justice services and thinks there is a problem with building another huge prison.

“It’s like a reverse Field Of Dreams,” he says. “If you build it, they will fill it. If it’s for 800, I guarantee you that in three months it will be full and if they build it with a 1,200 capacity, within three months that would be full too.”

Mr Gardner, who is an adviser with the Community Justice Scotland, says he wouldn’t have built HMP Glasgow in the way it is being envisaged and would build smaller custody units instead. “The really dangerous people,” he says, “I have no issue – I want those people in jail. But where you don’t present an imminent risk of serious harm, all bets are off – everything below that is manageable in the community.”

Dr Philippa Tomczak, an academic who researches prisons and their effects, agrees. “No changes to Barlinnie’s physical infrastructure will be able to overcome the inherent problems of having a large prison population,” she says. “Scotland has had the highest imprisonment rate in Western Europe for some years and almost 25 per cent of these prisoners are on remand so may not be found guilty of any crime.”

Like Keith Gardner, Dr Tomczak, who is based at Nottingham University, believes much smaller units would be a better solution. “Barlinnie is already a very large prison, holding over 1,400 men,” she points out.

“After the 1990 riots at Strangeways, Lord Woolf recommended that prisons should all be limited to 400 men in order to maintain order. While overcrowding is a serious issue, building more cells facilitates them being filled and ultimately overcrowded once again.”

Then there is the issue of who we are sending to the cells in the first place. For a start, there is that high proportion of the population who are on remand – effectively one in every four people in Barlinnie is untried and unconvicted. Then there is the issue of short sentences – there is now a presumption in Scotland against sentences of under a year but a large part of the Barlinnie population is still in prison for months rather than years.

Crime prevention

NATALIE Logan MacLean believes we should also be trying to spot the kind of men who will end up in Barlinnie from a very early stage in their lives to try to stop them getting into trouble – and she knows this because of what happened in her own life. Her dad had issues with addiction and served time in prison, leading to her struggling at school.

“My behaviour at school was atrocious,” she says, “because I was continually in flight or fight worrying about what was happening in my family home. I couldn’t concentrate because I was thinking what’s happening with my mum, is my dad OK, are my grandparents going to come and get me from school today. I was consistently worrying about my home environment.”

She says that kind of behaviour can be recognised at school and can be a red flag for trouble later in life. If you’re excluded by the first year of secondary, you have a high chance of ending up in prison. Logan MacLean believes more should be done to recognise kids in these kind of circumstances and give them the help they need. What that could mean in the longer term is fewer people engaged in crime and fewer people in Barlinnie.

But let’s be realistic: prisons will always be needed and some people will end up in them. Which leads to the next question: what should those prisons be like, what should the conditions be like? The last letter Logan MacLean and her family received from her father included complaints about the conditions in jail. He said the system was not going to beat him but a short while later he committed suicide.

She says it is largely because of losing her father in this way that she has the drive to improve the system and adds that has to include the conditions in prison buildings Barlinnie was and is notorious: slopping out only ended in 2005 and the prison has been criticised for still using holding cells which the prisoners call “dog boxes”: cramped, dilapidated, often dirty mini-cells where the prisoners hand over their clothes in exchange for prison uniform.

Logan MacLean’s reaction to all of this is blunt. “If you put someone in prison and you treat them like a dog, they are going to act like an animal,” she says. “But if you treat them like a human, you’re going to get a very different response.”

For a start, that means putting men into cells that are appropriate for them – in some cases, it will be single cells but for other people too much time on their own can be a problem Logan MacLean, who has also struggled with addiction in the past, knows herself that it is often when she is alone at night that negative thoughts can get control of her.

Keith Gardner says the design of the building is an important place to start. “Barlinnie is unique because it’s different from any other prison in Scotland,” he says. “The flavour of it, the sheer volume and turnover. It’s full of good people in a bad system.” He also says it doesn’t compare well with prisons like Low Moss in Bishopbriggs which opened in 2012.

“At the front end of Low Moss, you can’t miss it’s a prison – you go through scanners and there’s bars and all the rest of it but once you get into the heart of Low Moss, it has the feeling almost of a new college – big, high, light atriums –and the culture is different because it was created as a new prison. They’re committed to the likes of education.”

Food for thought

AT Barlinnie by contrast, he says the men are fed in their cells at 5pm and refer to it as “the feeding” (that parallel with animals again). At Low Moss on the other hand, there are communal areas which lend themselves to more normal behaviour. The messages are entirely different but equally powerful “If you’re in a crap environment, people can think it says something about them,” said Gardner. “This is as good as we need to treat you.”

Keith and others also believe that a better, more caring, culture should extend to the cells themselves. It hasn’t been confirmed yet if it will happen, but the hope is that HMP Glasgow will have landlines and screens in every cell. The think tank Reform Scotland has conducted work in this area and its research director, Alison Payne, says it is important to recognise how technology has changed. She says we are probably all familiar with seeing prisoners queueing up to use the phone in shows like Porridge but that was at a time when even people outside prisons had to queue up to use a phone as well. But now the world has changed.

“One of the things we’ve pushed on is to allow landlines in cells,” she says. “It can be a difficult sell to the public when money is tight but ultimately one of the aims of justice is to prevent reoffending and one of the big things that can help rehabilitation is maintaining family links.” A landline in your cell can dramatically help this, she says. Screens can also be used to make education more accessible and easier. Naturally, who you could call and which websites you could visit would be restricted.

Elsewhere in prison, Logan MacLean says it’s important to put recovery from addiction and drugs at the heart of any new jail and would like to see a dedicated “recovery wing” in the new HMP Glasgow. She says it amazes her that in all the time she herself struggled with drink and drugs, no-one ever asked her what had happened in her life to make her use alcohol and drugs as a coping strategy. A recovery wing would provide a chance to do that with prisoners and hopefully release men who are better able to cope than they were when they went into jail.

Another issue is ageing and health. One of Barlinnie’s most famous inmates was Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed al-Megrahi, the man convicted of the Lockerbie bombing who was released on compassionate grounds after being diagnosed with terminal cancer. Keith Gardner has been involved in other cases of prisoners who have sought compassionate release and says the system is tortuous and difficult. This is despite the fact that with an ageing prison population it is likely to become more of an issue. Prisons are not set up for pensioners, he adds.

Toxic cycle

WHERE prisons are also falling down, he believes, is when they release their inmates back into the community and, without a rethink, it is a problem the replacement for Barlinnie may well repeat. There are some signs of hope – the new Bail and Release from Custody Bill, for example, will ban releases on a Friday which can make it difficult for former inmates to access services at a weekend. There have also been some improvements in co-ordinating services such as housing and health to help prisoners when they get out – but it’s patchy. There is also no legal mandate to help, as there is with child protection, for example.

One potential model for improvement that often comes up is Finland which in many ways is comparable to Scotland, in good and bad ways. Its population is similar and the country also has its problems with drink and drugs. But it only has about 4,000 in prison – around half the number in Scotland. Understanding why that may be could help change the culture in and around new Scottish prisons like HMP Glasgow.

“The mentality in Finland is that prison should be for people who present as a risk to other people,” says Keith Gardner. “They also view drugs as truly a public health issue. And they understand isolation and exclusion so their infrastructure is much more co-ordinated. What they do is early-doors connection with services and the services are connected into the community – they have one agency that deals with it. One agency controls both the prison and the community side of it.” It makes it easier for an ex-prisoner to know who he or she needs to go to for help, Gardner points out, and he believes it can also make it easier for the ex-con to stay out of prison for good.

Everyone accepts that it will not necessarily be easy to move to such a model in Scotland even though HMP Glasgow is a good start. For example, you still have short sentences being handed out.

The middle ground

KEITH Gardner also points out that there is still a strong socially conservative streak in Scotland that resists the idea of “soft options”. He says there will always be a section of society that feels this way and another libertarian wing that doesn’t believe in prisons at all. Neither is right, he adds, and he believes there is a compassionate, workable solution somewhere in the middle. “Prisons are a necessary evil,” he says, “but they don’t necessarily have to be evil.”

Gardner also believes the new HMP Glasgow is a tentative sign that the message is getting through but says we have a justice system that is in evolution when it needs to be in revolution. It is still possible to serve a sentence – short or long – without doing any educational or rehabilitation work at all. It is still possible – even probable – that you can go into prison with a drug problem and come out with a worse one. And it is still possible that prison will cut you off from all the people, or services, that could help you. Everyone – or almost everyone – agrees that has to change and Glasgow’s new prison is a small step towards making that happen.

But, as usual, it will require more resources. Building the new Glasgow prison is going to cost £100 million but money also needs to be spent on making the services in and around the prison better too. Gardner says if you treat people more humanely, it genuinely makes them feel better about themselves and if you help them in prison, it can make it less likely that they will end up coming back. And that surely is the point of prisons, old and new, isn’t it? We accept that we need prisons but do we accept that we need to change them so that fewer people go there.

A Scottish Prison Service spokesperson said: “The new HMP Glasgow will be designed to deliver safe and secure accommodation for those in our care, in a way which gives them the maximum opportunity for successful rehabilitation and positive outcomes.

“The needs of our surrounding communities has also been a key consideration from the start of the development process.

“We have liaised with partners and community groups at this early stage, as we move into the design phase, and will continue to do so throughout to secure lasting benefits.

“The design and construction of HMP Glasgow provides an opportunity for SPS to explore digital solutions to ensure a prison which is fit for the future.

“The anticipated completion of construction in 2026 offers the opportunity to keep pace with, and inform, current developments such as in cell telephony and future ambitions.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel